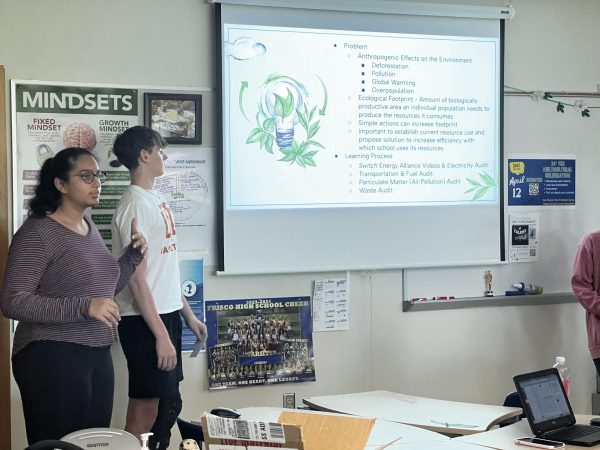

She stood with her group (missing a member) in front of the entire class, with a district administrator looking straight at her.

She was forced to present her part thoroughly, and the part of her absent classmate, with only a few notecards in her hands and a limited amount of words written on the slides.

The nerves started to take control, but a weird mix of comfort was attached, too.

A mix of comfort that would’ve been beneficial during her presentation to the Indian Agricultural Research and Development Community.

Senior Madhumita Manthri hasn’t always been very fond of her family’s farm in India.

“During my eighth-grade year, my parents went to the farm every weekend while I stayed home,” Manthri said. “But one day my dad dragged me to show me what the farm looked like. And dragged me back the next weekend. And the next.”

It was a good thing he did.

Manthri started going back to the farm willingly after a few forceful visits and started to love and appreciate its beauty and complexity. Once acquainted with the farm, she involved herself with different farm activities and explored ways she could assist her dad with management and cultivation of the crops.

“Exploring the management of the farm made me aware about a problem our farm faced: water resource management,” Manthri said. “A lack of this sort of management can deplete resources so I wanted to do something to help.”

Manthri moved to the United States before the start of her junior year. When she went back to India to visit during the summer, she created a small scale Arduino Motor Irrigation System.

Using her knowledge from building an Arduino motor LED lightshow, she experimented on the farm by connecting the motor to four crops and using precision technology.

“In scenarios like this, precision technology is critical to use, because, while irrigating a lot of water, which was something I was working with in this case, I needed to set a target so extra water wouldn’t slip out,” Manthri said. “If my small scale, cost-efficient Arduino motor works in the scale it’s being experimented on, there’s a possibility that the scope can be increased, which means this motor could be successfully integrated in larger farms.”

Manthri’s contributions to the farm sparked her interest in climate and agriculture.

With the help of her older brother, who currently attends Cornell University, Manthri also created a Machine Learning Crop Predictor Model which helps predict ideal crops for a particular region given inputs like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK) levels, soil type and humidity.

Manthri’s inventive spirit scored her an internship at RenKube in Bangalore, India, a company which specializes in agritech, where she worked on their crop yield data. She also had hands-on experience with the testing of solar panels in different regions.

“Working on their crop yield data ultimately led me and my mentor to present our findings to the Indian Agricultural Research and Development Community,” Manthri said. “Presenting in front of a very intimidating audience full of authority figures was nerve-wracking, but thrilling.”

When Manthri returned from her summer in India, she knew she made the right decision taking AP Environmental Science as one of her electives.

“I wanted to learn more about something that aligned with my interests,” Manthri said. “In college, I might not get the opportunity to take a similar project-based class like APES, so I wanted to take the opportunity when I had it.”

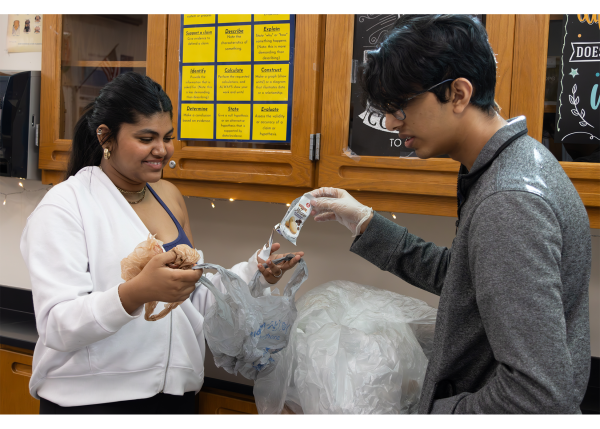

And she indeed seized the opportunity. In October, Manthri was given instructions to participate in a group project for the class. Her group was responsible for choosing an audit to focus on and investigate.

“Out of the five audits: electricity, waste, air quality, water and transportation, we decided to go forth with transportation,” Manthri said. “Most groups were doing electricity and talking about how they could change the way projectors work or how they could replace the current hand dryers. I found that to be very repetitive. Transportation is something that many groups didn’t do and I myself am an advocate for walking. I don’t even like to drive at all. I don’t have my license as a senior and just have my permit for ID purposes.”

Throughout a three week period, Manthri’s group started to tackle a problem regarding the district’s transportation department that had impactful effects on the school.

“FISD itself has a high ecological footprint,” Manthri said. “An ecological footprint is basically how much of a nuisance you are to the environment and even though the district may have a high ecological footprint, Frisco High School’s is higher.”

This high ecological footprint is associated with the extensive amount of pollution that cars and buses bring in.

“We want people to use more buses because there are less vehicles,” Manthri said. “You see so many cars in our parking lots, even though ideally we should be using school buses. However, school buses are still not good because they emit a lot of greenhouse gasses.”

Manthri’s group investigated the district’s transportation department — specifically searching Frisco High’s records — by collecting data on how many gallons of fuel were being used on the buses going to and from Frisco High. Manthri’s group found solutions to limit the consumption playing into the emission of carbon dioxide, a significant greenhouse gas, which contributes to global warming.

“Ultimately, we came up with a solution that had to do with carpooling and the transition to electric buses in the district,” Manthri said.

Then there was the presentation.

“I was pretty nervous to present in front of admin because one of my groupmates was absent so I had to cover for him,” Manthri said. “But there was this weird sense of comfort presenting up there because all groups were presenting and being one of the last ones allowed our nervousness to die down.”

The presentation itself was visually appealing — there were few words, a color palette, and many graphics and graphs. Throughout the presentation, three solutions were explored: the transition to electric school buses, route optimization and carpooling.

“Each solution was explained thoroughly,” Manthri said. “We weighed the pros and cons of all three. For example, transitioning to electric school buses comes with pros like reduced greenhouse gas emissions, a reduction in noise pollution, and long term cost saving. While, the cons for such a solution were high initial costs, limited range and charging infrastructure and dependence on the electricity grid.”

The group also emphasized that carpooling is encouraged for students who live nearby one another.

Ultimately, the group proposed a combination of all three of those solutions.

“There is no one main or ideal solution,” Manthri said. “To come up with a practical solution, it is important to combine all of the three solutions into one single proposal as a combination of all three will surely bring the change required throughout the school and district.”

The presentation went well, per Manthri’s expectations, even if the administrator didn’t show much of a response toward their proposal.

“I’m just glad that it’s all over,” Manthri said.

Now, the APES classes have finished taking their end of semester exams and are currently studying biomes.

“Our current unit also has a project associated with the curriculum,” Manthri said. “I know this project will be, once again, tiring — like many previous ones — but I wouldn’t change how my farm brought me to this class for anything.”

![Audra Shioya '25 receives a big check as a scholarship recipient. [PC: Audra Shioya]](https://raccoonrambler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/IMG_4100-900x1200.jpeg)